TRIGGER WARNING: Chronic pain, details of injury, mentions of surgery, suicide and child loss.

“At the end of the day, we can endure much more than we think we can.”

Part One.

Pain and the Patriarchy

In December 2024, Labour MP and Chair of ‘The Women and Equalities Committee’ (WEC), Sarah Owen, released a statement sharing the findings of the committee’s long awaited inquiry into misogyny in medicine. The inquiry was set in motion as a response to Nurofen’s Gender Pain Gap Index Report in 2022, which revealed that women wait longer for a diagnosis than men for the same type of pain.

The ‘Gender Pain Gap’ refers to the phenomenon in which pain is more poorly understood and mistreated in women due to “systematic gaps and biases”. The fact is, more women than men feel their pain has been dismissed or ignored, and more often than not, this term is used in reference to gynaecological pain.

The WEC report found that up to 1 in 3 women live with heavy menstrual bleeding, and/or suffer from a gynaecological condition such as endometriosis or adenomyosis. The report states that 30-40% of adolescents miss school because of period pain, and The Bupa Wellbeing Index claims that almost 50% of women in the UK experience severe pain or cramps every month during their period.

“Women are finding their symptoms dismissed, are waiting years for life changing treatment and in too many cases are being put through trauma-inducing procedures. All the while, their conditions worsen and become more complicated to treat.”

Sarah Owen MP

Women struggle with pain and discomfort that interferes with every aspect of their daily lives, from their education and career, to their relationships and fertility. We are more likely than men to suffer headache disorders such as migraines, as well as lower back pain, caused perhaps from working at desks in office spaces built with men in mind. If you are a woman, it’s likely you have a stash of paracetamol or ibuprofen in your bag, and it is also highly likely you have taken a pain killer in the past month. As Miranda Larbi wrote in a recent article for Stylist , “even if you’re healthy, active and not living with a diagnosed pain condition, it’s likely you still live with a semi-regular threat of pain”.

The normalisation of women’s pain stops women seeking a diagnosis. In another recent article for Stylist, Lauren Gaell writes about the years it takes for women to receive a diagnosis for their pain - an average of almost nine for an endometriosis diagnosis! It is no wonder, Lauren writes, that “74% [of women] choose self-care over seeking professional healthcare”.

In This Won’t Hurt: How Medicine Fails Women, author Dr Marieke Bigg describes the medical landscape today as one “designed for, and by, men”. Marieke’s book emphasises that medicine “is not and has never been gender neutral, from research to treatment to diagnosis.”

“The idea that a woman is defined by her childbearing capacity is pervasive in our world. This is as true of medicine as it is of culture at large, but given the subtle and entangled ways in which people learn about these ideas, repeat them and internalise them until they feel so true they can only be natural, it can be hard to expose the sexist assumptions that travel between culture and medicine.

Dr Marieke Bigg, This Won’t Hurt: How Medicine Fails Women

This sentiment is further examined in Elinor Cleghorn’s excellent book, Unwell Women: A Journey Through Medicine and Myth in a Man-Made World. In the book, Elinor explores how biased gender expectations directly affect how serious and deserving of treatment a women’s pain is perceived to be, and sadly but unsurprisingly “women’s pain” is far more likely to be seen as having “an emotional or psychological cause, rather than a bodily or biological one”. That’s without accounting for the insidious impact of structural racism, of which there are many devastating examples of injustice and mistreatment that far outweigh that of White women.

Put plainly: Women and their pain are not taken seriously.

This, of course, is nothing new. Since Eve nibbled that damned apple and Pandora opened that bloody box, women have been vilified and their pain deemed their natural punishment. From the wandering womb of Ancient Greece, to the rise of witch trials in Medieval Europe, through the dawn of hysteria, to the modern day understandings of autoimmune diseases, the menopause and endometriosis, biological theories about female bodies have been used throughout history to reinforce and uphold constraining ideas about women.

Pain is a physical, mental and social issue, yet today in the West, despite our modern freedoms and illusions of bodily autonomy, we continue to be defined by, and sadly it seems, to define ourselves as women, by our genitalia and our ability to reproduce. We continue to accept pain as a natural state of womanhood. A state that can not be healed.

“Women are born with pain built in.”

Belinda, Fleabag (2016)

Part Two.

Painting Pain

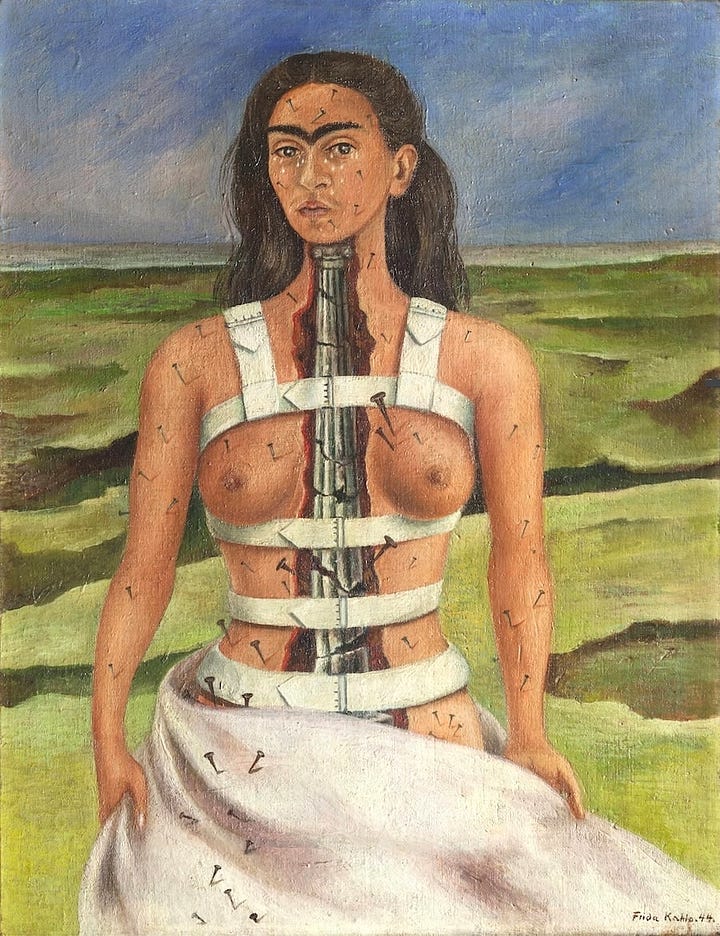

If there ever was a woman who knew pain it was Frida Kahlo.

As a child, Frida suffered with Polio, leaving her right foot and leg crippled, with a limp for which she would be mocked by classmates. In 1925, when she was 18, her body was crushed when the trolley car she was riding hit another vehicle. An iron handrail impaled her pelvis, fracturing the bone, as well as her legs, ribs, and her collar bone in several parts. In her lifetime she underwent 35 surgical operations, suffered two major depressive episodes, suicide attempts, identity issues, relationship struggles, and child loss.

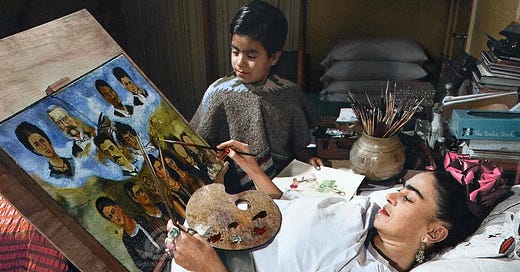

Following the trolley car accident, Frida spent three months immobilised in a full body cast. It was here she began to paint. Her father gifted her his old paints and her mother had a mirror mounted above her bed. As she was so often alone, she would paint herself.

“I paint self-portraits, because I paint my own reality. I paint what I need to. Painting completed my life.”

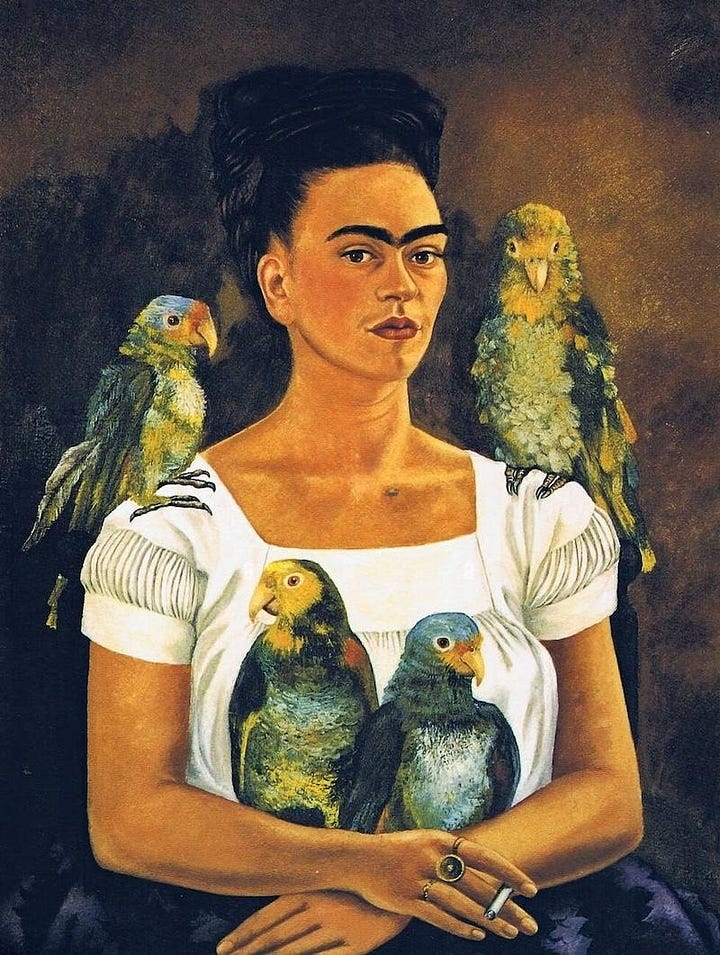

Between the ages of 18 and 47, Frida created 143 paintings, 55 of which were self-portraits. Her paintings boldly carry the message of her pain, and the themes of love, loss and rebirth, with an authenticity and bravery that continues to strike us, shining a light on what so often lies unseen.

Frida Kahlo was a woman who broke taboos, not only in regards to her art but also her style, her identity, her distinct brand of femininity, and her strength. An unapologetically authentic woman with big hair, big trousers and one big, beautiful eyebrow. Her work celebrated life, nature and her mexican heritage. She experienced chronic pain throughout her magnificent life, but never let her pain define her, despite her grief.

“Everything can have beauty, even the worst horror.”

Part Three.

A Movement

For Frida Kahlo, art was a form of therapy. She is an icon to many chronically ill and disabled people, particularly women, who find meaning and comfort in creativity as a way of expressing their pain when there are no words, or when they simply go unheard.

In the spirit of Frida, high profile figures including Selena Gomez and Lady Gaga, have begun to speak openly about their pain, living with Lupus and Fibromyalgia respectively. BBC News broadcaster, Naga Munchetty lived with severe pain for 32 years before being diagnosed with adenomyosis. She was told (gaslit) repeatedly by her GP that her symptoms were “normal”. Naga is one of many women pushing for reform in medicine and education here in the UK, appealing for a move away from painful and invasive procedures, towards research that will provide women with quicker and more accurate diagnosis.

Our current system of treatment and diagnosis relies far too heavily on research conducted into male medicine. Heart disease, attacks and failure are no less common in women than in men, yet women wait far longer for an accurate diagnosis due to our symptoms differing from those of our male counterparts - the so called “average patient”. This is not minor inconvenience, this is life or death.

I get it, we don’t want to complain, we don’t want to make a fuss for fear of being accused of overreacting, being labelled “overly emotional” or god forbid, “difficult”. We accept to a degree, that pain is a natural and even defining characteristic of the female body.

You are not alone in your pain. Change is in motion.

"I used to think I was the strangest person in the world but then I thought there are so many people in the world, there must be someone just like me who feels bizarre and flawed in the same ways I do. I would imagine her, and imagine that she must be out there thinking of me, too.”

Further Reading

this was so beautifully written oh wow